As AI models increasingly succeed on long, multi-step real-world tasks, traditional mechanistic interpretability—focused on single-step, static analysis—no longer suffices. Long-horizon, agentic behavior introduces planning, commitment, and failure modes that only emerge over extended trajectories. Understanding and improving these systems requires new interpretability methods that track evolving internal state across time, identify decision-critical moments, and enable mid-trajectory intervention. Bridging this gap between short-horizon interpretability and real-world agent performance is now a central challenge for the field.

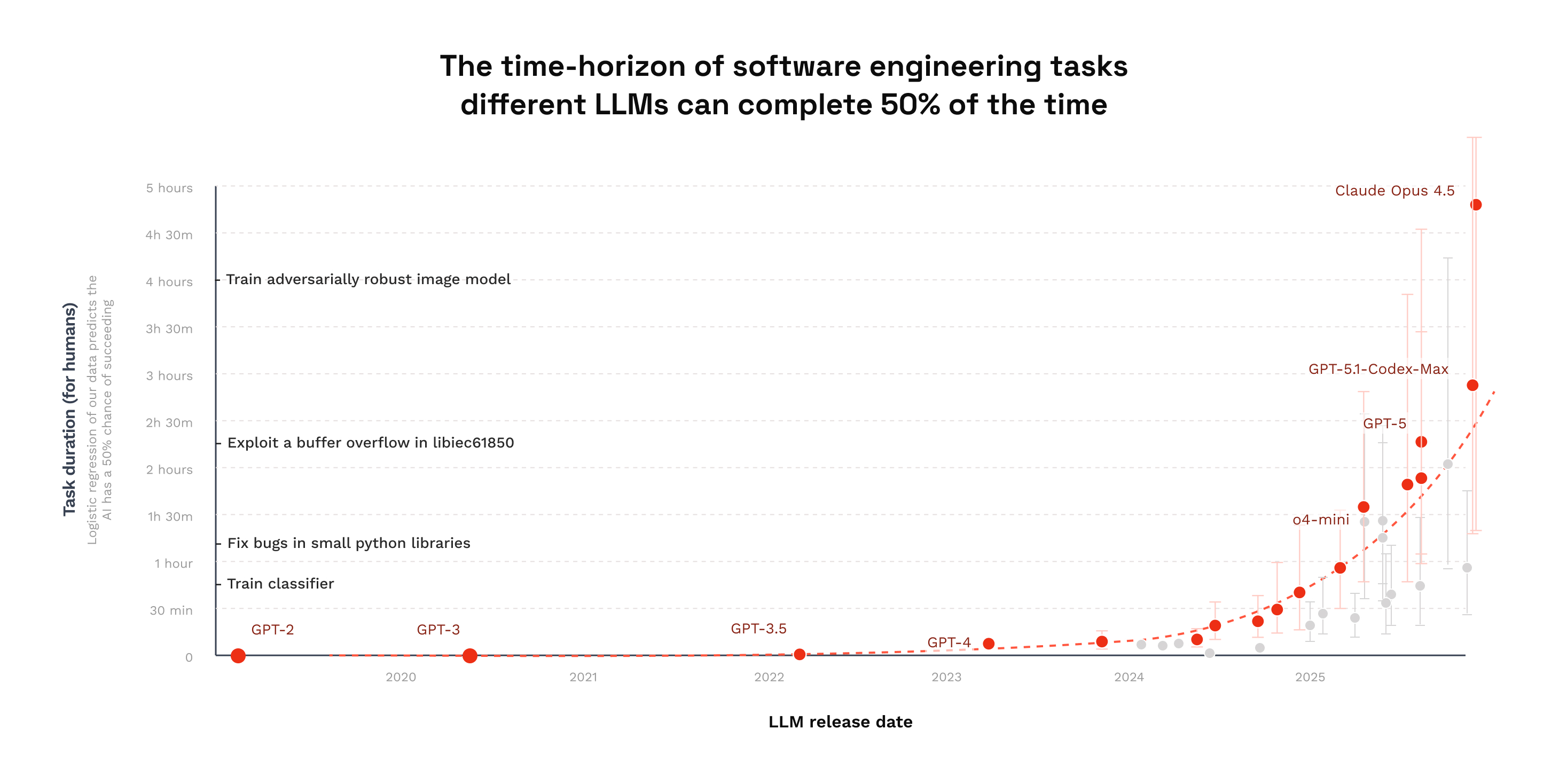

The length of real-world tasks that models can reliably complete doubled between and 2023 and 2024 and again in 2025. As model capabilities increasingly emerge over long-horizon tasks, interpretability remains focused on short-horizon settings.

In current practice, mechanistic interpretability (MI) primarily analyzes models in static, short-horizon settings: predict the next token, analyze activations for a single pass, or interpret local circuit effects for one question and one answer. This made sense when models were evaluated on short, isolated benchmarks. But as models develop into agents (that is systems that plan, act, observe, and adapt over many steps) their capabilities are no longer well-captured by single-turn evaluation. The capabilities of AI systems aren't static — they grow with the length of the tasks AI can complete.

This transition from static to dynamic interaction could surface behaviors and latent mechanisms that are both scientifically rich and practically important, enabling lightweight interventions that improve agent performance and workflows. For example, a SWEBench coding agent may repeatedly apply reasonable patches while remaining committed to an incorrect bug hypothesis, even as new test failures provide contradictory evidence, eventually looping without progress. Analyzing logits or activations for any single edit explains what the agent did, but not why external feedback stopped updating its internal beliefs. Only by tracking internal representations across tool-augmented trajectories can we identify when evidence ceases to influence the model and intervene.

New Paradigms with Long Horizon Tasks:

Planning as a Persistent Internal State

Long-horizon tasks force models to do more than produce plausible local text; they must plan ahead, revisit and refine internal strategies as new observations arrive. Traditional next-token interpretability can highlight logits and attention for one step, but it cannot answer essential questions like: Which internal state supports planning several steps ahead? When and how does the model revise its strategy mid-trajectory?

Work on separating high-level planning from low-level execution shows that planning remains a bottleneck in long-horizon settings, even with sophisticated heuristics. These planning signals are inherently temporal and require interpretability methods that trace how latent representations evolve across many steps.

Temporal Credit Assignment and Latent State Evolution

In static contexts, attribution methods assume that most causality is local: input tokens directly shape outputs. But in long-horizon agentic loops, outcomes often depend on actions taken many steps earlier. This is analogous to the classic RL problem of temporal credit assignment, where the model must distribute “blame” and “credit” across long sequences. Success rates on long tasks reveal that early decisions shape later success or failure in non-trivial ways.

Failure Cascades

Long tasks reveal structured failure modes that are invisible in short evaluations. Small errors such as misinterpreting a tool’s response, misunderstanding a goal constraint can compound into looping behavior, dead ends, or catastrophic cascades. Some long-horizon execution studies argue that failures stem more from execution than reasoning capability per se. Interpreting these cascades requires tools that can detect when internal representations lose coherency and how the model’s latent variables diverge from a successful trajectory. Without long trajectories, such patterns simply don’t emerge.

New Interpretability Methods

Long-horizon agentic tasks demand new interpretability methods that operate over trajectories rather than isolated forward passes. As agents interact with environments over many steps, internal state evolves, accumulates commitments, and selectively incorporates evidence in ways that static analysis cannot capture. Existing interpretability techniques, largely designed for single-step settings, must therefore be stress-tested and adapted—or replaced—to remain informative in this regime.

One illustrative approach is to narrow interpretability to the most consequential parts of an agent’s execution. By identifying high-value segments of a trajectory, for example, timesteps where small perturbations would significantly alter the final outcome, as measured by a trajectory-level value or importance signal, causal attribution techniques can be applied to decompose the model’s internal computation at those points. Focusing analysis on decision-critical segments makes circuit-level investigation more tractable and highlights where current methods succeed or fail when scaled to long horizons.

More broadly, long-horizon tasks act as a forcing function for interpretability research: they expose the limitations of existing methods and motivate the development of techniques that can track, aggregate, and intervene on internal state across extended trajectories.

From Interpretation to Intervention

Once agent behavior is analyzed at the trajectory level, interpretability shifts from explanation to control. Long-horizon interpretability reveals when internal state drifts, overcommits, or stops incorporating evidence, creating direct targets for intervention during execution rather than after failure.

Coordination with External Tools and World State

As illustrated by the earlier SWEBench example, failures in tool-augmented coding agents often arise from misalignment between internal representations and the external world state produced by tool calls. An agent may continue modifying the same function despite test outputs indicating that the failure originates elsewhere.

Static interpretability can explain individual edits, but not why external feedback ceases to update internal beliefs. By tracking internal representations across tool interactions, long-horizon interpretability makes these state-tracking failures legible and enables mid-trajectory interventions that restore alignment between latent state and world state.

Self-Monitoring and Early Failure Prediction

Long-horizon coding agents often exhibit detectable internal signatures several steps before failure. For example, an agent may repeatedly rerun tests and apply increasingly localized patches without revisiting its original hypothesis about the bug.

Decoding such signals mid-trajectory enables early stopping, replanning, or hypothesis resets, shifting failure handling from post hoc diagnosis to proactive control.

Conclusion

As models become agents, interpretability must become temporal. The mechanisms that govern success and failure of agents often live across long trajectories, not isolated forward passes, and understanding them requires fundamentally new approaches. Long-horizon tasks reveal both where current methods fail and where the highest-leverage insights lie.

This is why we launched the Million Dollar Mechanistic Interpretability Prize earlier: to focus attention on the gap between Mech Interp being used on real world tasks. Closing that gap is essential if we want interpretability to scale alongside model capability and we believe that it is one of the most important problems for the field to work on now.

We are working on tools to make it easier to do MI research in long-horizon tasks. Please reach out to mechinterp@withmartian.com if you would like early access.